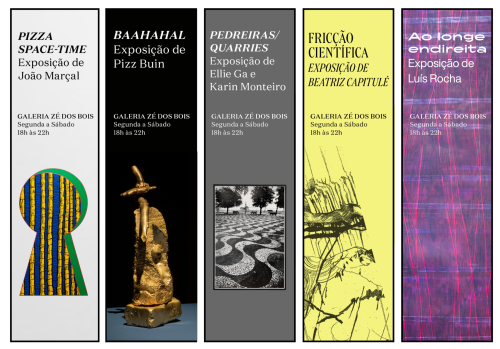

Baahahal

Baaaaahh

Ah ah ah ah

Is there cash for all the stash?

Hard is the brass

Soft is the bone

Only spare beans

The bread turned boodle

Out of the green

From chips to chin

From beans to the broth

And the poodle?

ITA Ita ufa UFO

From Gold to Gods, from Matter to Art

Chapter 32 of the Book of Exodus tells how the people of Israel, concerned about Moses’ prolonged absence on the mountain, went to his brother Aaron and asked him to make “gods” so that they would “go before” and guide the people. Aaron then asked the people of Israel to hand over the golden earrings they had brought from Egypt and used them to make a “molten calf.” He then built an altar and held feasts. But God on the mountain saw everything and ordered Moses to come down and punish the people for disobeying the second commandment (do not make images or worship them). In his fury, Moses burned the calf, ground it to powder, and strawed it upon the water, which he then gave the people to drink. When questioned by Moses about his actions, Aaron first blamed the people, which he said was “inclined to evil,” but then claimed that the image made itself: he just threw the gold into the fire, “and there came out this calf.”

Confronted with the absence of their god and mediator, searching for a divine presence, an indicative sign or image through which they could access it, Aaron and the people of Israel built the calf through a “value conversion” process from the gold they had gathered in Egypt. Lacking an image of Moses’ God, the people resorted to a traditional representation of one of the deities of their Canaanite neighbors, Baal (whose word means Lord, Owner), who was depicted as a calf. The “frenzy of the visible” reveals the unfeasibility of obeying the second commandment. Without an image, how can we reach the truth?

In the second chapter of his Theological-Political Treatise (1670), Spinoza addresses the issue of the “form” of God’s revelations to the prophets. According to the philosopher, “God is only revealed to the prophets according to the tenor of their own imagination.” There was a correlation between the type of images revealed and the prophet’s ability to receive them: “if the prophet was a country fellow, it was oxen and cows and so on that were what was represented to him; if he was a soldier, generals and armies; and if he was a courtier, a royal throne and such like.”[1] In Moses’ case, since he had no image of God formed in his brain, God did not appear to him in any form when Moses asked him to let himself be seen. And because he believed that God was in heaven, God revealed himself to him coming down from heaven on the mountain. Therefore, and because he was somewhat limited in his imagery, Moses had to ascend the mountain to speak with God, “which he would have had no need to do had he been able to imagine God readily everywhere.”[2] From this, Spinosa concludes that the prophets knew no more than other people and that the forms that the revelations took were somehow “irrelevant” since they were only ways of taking in, through human imagination, a simple message from God.

Following this reasoning, the words and images delivered by the prophets do not reveal a truth about God; they reveal themselves as constructs. Despite their claim to revelation, these images were fraught with uncertainty. That’s why prophets often asked for a “sign” to assure them they were speaking with the “true” God. This is one side of the “aporia of representation” that Fernando Gil addresses in his Mimesis e Negação (1984): the objectivity and truth of a representation are called into question by the subject’s constructive activity.

The golden calf is a classic episode where one can witness a tension between power, representation, and matter — or subject, image, and medium — and the coexistence of extremes in the same object: the creation of images and their destruction, the visible and the invisible, the material and the immaterial, the animate and the inert. What is unacceptable in the eyes of God and Moses (and seductive to the others) is that the image of the calf not only represents divinity but is itself “divine flesh”[3] — “make us gods,” the people told Aaron. The calf is sacred not because it represents God or because it is made of gold, but because it is a divine image — the material object and the image it supports. The image is so powerful that it competes with God as his rival. Its materiality manages to make visible what is supposed to be invisible, manages to make divinity present. This paradox, the concomitance of concreteness and abstraction, also characterizes art.

A Pizzbuinian intervention in this story could invite a laugh, a glitch in the word Baal that turns the Lord into something closer to a talking animal. Pizz Buin may fall into this idolatrous temptation. Still, they do so through an “iconoclash” (borrowing from Bruno Latour), a constructive destruction, an ambiguous place of destruction/creation: art can originate in its own destruction, the image can reinvent itself and reproduce itself as an image based on the destruction of the image itself.

The pieces presented in Baahahal fuse all our gold into a form in a permanent, tangible search for an image. Like the calf, they are given as created by human hands and as self-made. Here, shapelessness is not a negation of form; and if it is, it is of a former form. Instead, it is an affirmation of form as a process of image creation. It is matter in the fulness of its autopoietic potency — it is an excess of matter overflowing out of itself, constituting itself as image and support simultaneously.

Baahahal proposes the veneration of a form that lives on the shapeless. It is a totem of unrecognizable bodies. The work itself establishes a space of search for a potential image. An image-that-has-been transformed into an image-to-be, or into an “art yet to come” already tested by the furiousness of its appearance’s impact. Only by granting matter the freedom to go through all possible forms can one aspire to go “beyond” matter. “Beyond matter” is a “before form,” a form in constant creation/destruction.

This is a reversal of the alchemical process, a mode of work through which one returns raw materials to their unfinished character, the visible creative potency they have as Matter. In this case, the creative fire generates a process of dedifferentiation, a regression to a previous stage that allows matter to transform into something else — a continuous process of becoming-other.

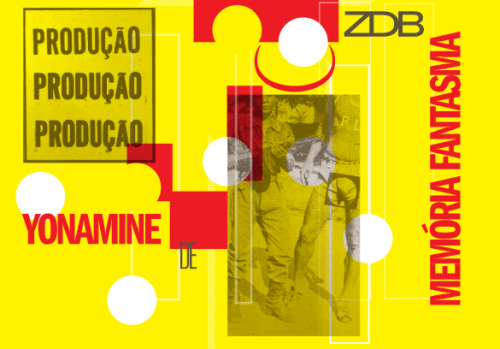

These pieces point towards a possibility of simultaneous coexistence of the multiplicity of forms, towards a unity of matter, which finds some parallelism in the various mountain-shaped “totems of concepts” that populate the most recent Pizzbuinian publication, Calhamaço (2023). Stacked between the bottom and the top of these mountains of concepts resting on each other one can find, for example, “seeing,” “believing,” “appearing,” “faith,” “technology,” “loose things,” “collective stories,” “community” … In this publication, we also find a profusion of images of statues, Venuses, Maries, Colossi, or proto-historical verracos, with their bits and limbs scattered across the pages, between knick-knack and chimera.

Forms may vary, but the golden calves remain. Images will always “go before” us as guides. We can ask ourselves, like in the first pages of Calhamaço, “How high on the mountain are we? / Do we want to go up / Or do we want to go down? / Walk around / bring a map? Or make a map?”, because “There are many mountains you fool“[4] but not all of them have gods.

Text by Liz Vahia written on the occasion of the exhibition Baahahal, by Pizz Buin, presented at the Círculo de Artes Plásticas de Coimbra.

[1] Benedict De Spinoza. (2015). Theological-political treatise (p. 30). Cambridge University Press.

[2] Ibidem, p. 38.

[3] In the poem, The Penultimate Poem, Alberto Caeiro writes that the god’s anima is their own body: “For them the body is the soul / And they have consciousness in their own divine flesh.” Pessoa, F. (2007). The collected poems of Alberto Caeiro (C. Daniels, Trans.; p. 153). Shearsman.

[4] Pizz Buin (2023), Calhamaço, Stolen Books, np.