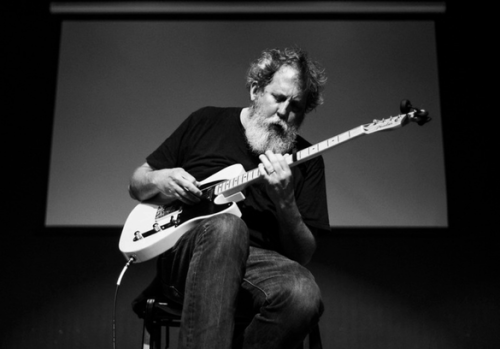

Self-proclaimed “Sir” because he can, this genuine globetrotter of real and imaginary worlds returns to Portugal in the wake of the release of ‘Hillbilly Ragas’ by Drag City. Hailing from the wide open landscapes of Phoenix, Arizona, Bishop was for almost three decades one of the three vertices of the Sun City Girls, alongside his brother Alan and Charles Gocher, until the latter’s untimely death in 2007, leaving in his wake a whole new way of creating, in a pan-global kaleidoscope that drew both from the dust of the most primordial American music, be it blues or jazz, and allowed itself to be contaminated by the rituals, scales, rhythms, and lineages of music from the most diverse latitudes—from Southeast Asian devotion to Central African drumming, with all the cardinal points in between — in a liberating act aligned with all kinds of esotericism, mysticism, an absurd and surreal sense of humor, and a constant capacity for reinvention and escape, paving the way for a legion of weirdos and explorers of the far reaches. Solo, he invokes for the guitar, mostly acoustic, all this plural vision, enchantment with the unknown, and ability to reconcile seemingly disparate worlds in a journey that starts from the already broad portraits of John Fahey’s American Primitive – ‘Salvador Kali’, his debut album was released on the latter’s Revenant label, which makes perfect sense – abstracts itself from fixed coordinates and chronologies to erect new realities. Throughout this time, and in parallel with collaborations with names such as Bill Orcutt in a duo or Ben Chasny and Chris Corsano in Rangda, he has promoted all kinds of bold and respectful crossovers on the six strings in albums such as ‘The Freak of Araby’ or ‘Oneiric Formulary’, in a kind of world folklore that owes as much to the swing of surf rock or the most hypnotic fingerpicking as it does to the lyricism of Egyptian music or Indian ragas. ‘Hillbilly Ragas’ opens up and at the same time reduces, not without some humor, these same intentions to a principle that is in itself somewhat absurd but with a grain of truth – and Henry Flynt’s hillbilly treatises opened up an immense panorama on the term – in an album that pulsates with that eternal sense of discovery that does not forget its founding roots but escapes acts of reverence or casual tourism, in a process of revelations that never forces juxtaposition, but finds the natural way to find meaning in its plurality.

BS