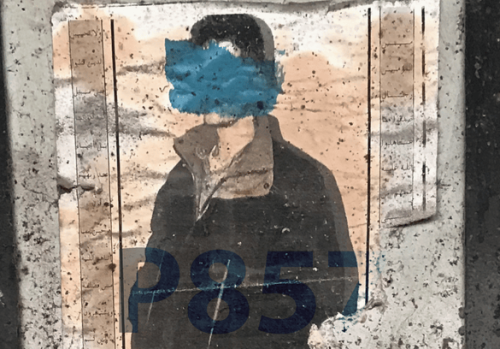

Cinema Troiano: Arquivos espectrais da Palestina (Trojan Cinema: Spectral archives of Palestine)

Programming by Cristina Hadwa and Raquel Schefer in dialogue with Laura Gama Martins

Mahmoud Darwish defined himself as a “Trojan poet” in “the camp of the losers,” deprived of “the right to leave a trace of their defeat,” inscribing his poetry in which Palestine is metaphor in the long and spectral “history of the vanquished.” More than seventy-seven years after the beginning of the Nakba, what can poetry do in the face of genocide in Palestine and the rupture of the link between seeing and acting? And what does “cinema of poetry” makes to the archives of history? Through a journey between the cinema of Jean-Luc Godard and Kamal Aljafari and the work of Basma al-Sharif, Maryam Tafakory, and Lincoln Péricles, this program focuses on the profanation of archives, in their materiality and spectrality, as an instrument for a rearticulation of aesthetics and ethics and for the exercise of justice in cinema from and about Palestine.

During the sessions, donations (free contributions in cash or via QR Code) will be collected for the Spanish NGO Paz con Dignidad for the Awda Association, which manages two hospitals and community care centers still operating in the Gaza Strip: more information here.

*

PROGRAM OF THE CYCLE:

SESSION 1

Monday, October 6, 2025, 10 p.m.

Notre musique, Jean-Luc Godard, 2004, France-Switzerland, screening of excerpts lasting approximately 20 minutes

O, Persecuted, Basma al-Sharif, 2014, Palestine-United Kingdom, 12 min.

UNDR, Kamal Aljafari, 2024, Germany-Palestine, 15 min.

Filme dos Outros, Lincoln Péricles, 2014, Brazil, 20 min.

All information here.

SESSION 2

Tuesday, October 7, 2025, 10 p.m.

Mahmoud Darwish: In the Presence of Absence, Maryam Tafakory, 2025, Iran-United Kingdom, 15 min.

Darwish, la reapropiación de la memoria-geográfica, Cristina Hadwa, 2020, Chile, 8 min.

Recollection, Kamal Aljafari, 2015, Palestine-Germany-Lebanon, 70 min.

All information here.

*

Mahmoud Darwish described himself as a ‘Trojan poet’ in “the camp of the losers,”deprived of “the right to leave a trace of their defeat.” He inscribed his poetry—where Palestine is metaphor—within the long and spectral “history of the vanquished.” In the poem ‘Eleven Stars over Andalusia,’ which laments the loss of Granada in contrast to dominant historical discourse, he wrote the verse “Truth has two faces”.

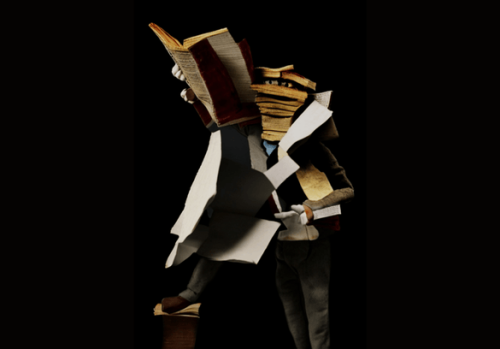

Obsessed with the lost text of the vanquished, the Trojan poet writes her own narrative, revealing the other face of the truth, which the present absentees—as some Palestinians, remaining present in the geography of the territory, even after losing their homes and lands, are called—also narrate. Expropriated but not defeated, the Trojan seeks to leave her traces. Darwish, who said his dilemma could only be resolved through language, alludes to the polysemy of the Arabic word “bayt“, which means both “house” and ‘verse.’ Poetry, then, becomes a house, where the Trojan poet finds her place. Cinema is also a place of encounter, as filmmaker Kamal Aljafari states, expanding the reflections of Theodor W. Adorno: “For a man who no longer has a homeland, writing becomes a place to live. I would say that, for Palestinians, cinema is a country.”

More than seventy-seven years after the beginning of the Nakba, what can poetry do in the face of genocide in Palestine and the rupture of the link between seeing and acting, which structured a fundamental part of post-war philosophical reflection? And what does “cinema of poetry” makes to the archives of history? Through a journey between the cinema of Jean-Luc Godard and Kamal Aljafari and the work of Basma al-Sharif, Maryam Tafakory, and Lincoln Péricles, the two thematic sessions of this program focus on the reuse and profanation of archives, in their materiality and spectrality, as an instrument for a rearticulation of aesthetics and ethics and for the exercise of justice in cinema from and about Palestine.

As a colonial ideology, Zionism is based historically on the denial of any possibility of self-representation by Palestinians, a premise that persists today in the systematic and calculated assassination of journalists and filmmakers in the Gaza Strip and the West Bank. In The Question of Palestine, Edward Said stated that “just as the specialised orientalist believed that only he could speak… for the natives and primitive societies he had studied—her presence denoting their absence—so the Zionists spoke to the world on behalf of the Palestinians.” If the existence of Palestinian cinema—in the same way as other anti-colonial cinemas throughout history—constitutes, in itself, an act of resistance, the films in the program, arising from that specific framework, as well as from the resurgence of forms of internationalist solidarity, re-inscribe the Palestinian people in the space of cinematic representation, a symbolic and metonymic re-inscription in their occupied territory. This gesture of justice is inseparable from the correctness of film forms.

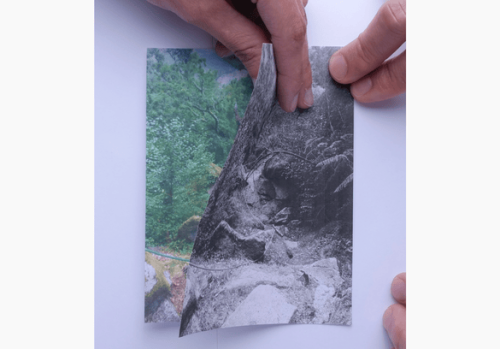

Continuing a genealogy that initiates with Dziga Vertov’s film practice and extends to Cuban noticieros, Lettrist and Situationist Cinema, as well as Mozambican newsreels, among other cases, the reuse—alongside the détournement and profanation—of archives in the films in the program is not only a procedure through which Trojan history, a counter-history, is carved out. It is also a film form, resulting at the material and enunciative levels of collective assemblage, that shifts the ontology of cinema to the terrain of spectral and speculative thanatology, between poetics and politics, presence and absence. “The Fedayeen—the sacrificed one—… knows that she will not see this revolution happen, but that her own victory consists in having started it. She may not know that her image, despite the Zionist barriers, will appear to you today,” wrote Jean Genet in The Palestinians. Trojan cinema, with its archives and spectral figures, between the home and the world, is one of the fronts where victory is played out.